Angela Nicholson looks at what you need to know to find the perfect printer

Given the huge number of printers on the market, deciding exactly which one is suitable for the job in hand may seem daunting, but this article will make things a lot simpler.

Print size

When anyone asks me for advice about buying a printer, my first question is usually, what size of print do you want to make? It is surprising how little thought many people have given to this matter, but it is a very important consideration.

Perhaps the first, but rather obvious point to remember is that while a larger format printer such as an A3+ or A2 model can be used to make smaller prints, an A4 printer cannot be magically scaled up to make A3 prints.

As well as weighing up the pros and cons of each printer size, the key to making a decision is to work out what size the majority of the prints that you want to make are likely to be. If you wish to fill albums and mantel-shelf-sized picture frames with 6x4in and 5x7in prints and make the occasional A4 print, there is little point in buying an A3 printer.

A2 printers

The high pixel counts of modern DSLRs lend themselves to making larger prints and manufacturers like Canon and Epson are gearing themselves up for increased sales of A2 and large-format printers. If your aim is to produce lots of prints to display in an exhibition or for sale, A2 prints have much greater presence on the wall than A3 prints. They make a bolder statement and, for some people, indicate a higher level of work. It’s worth bearing in mind that the framing costs are also much higher, though.

A4 printers

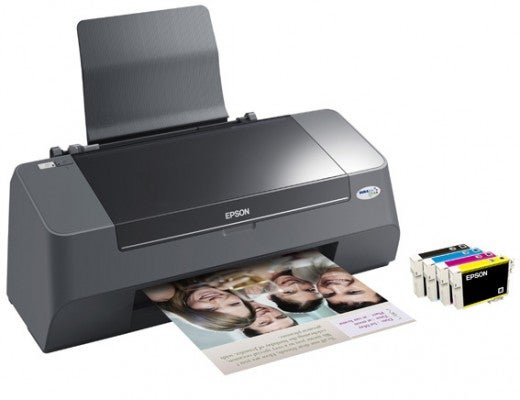

There are comparatively few dedicated A4 printers available these days, as the majority are part of a multi-functional unit that can also scan documents and in some cases send faxes.

In the past, the printers and scanner units built into a multifunctional or all-in-one device tended to be second rate, with older components being used while the current technology was reserved for dedicated units. Thankfully, this is no longer the case, but it is important to distinguish an all-in-one that is meant for office use from one that is aimed at more demanding photographers.

Printer inks

Many general-purpose printers use a limited number of inks, and sometimes there may be just four, comprising black, cyan, magenta and yellow. The inks may also be contained in just two cartridges, one for black ink and the other for the coloured inks.

This approach can be extremely wasteful as the coloured ink cartridge has to be replaced as soon as any one of the three colours becomes depleted. Separate ink tanks are a far better option for photographers as they allow the cartridges that still contain some ink to remain in place while only the depleted one is replaced.

Adding extra ink colours to the basic set, for example light magenta, light cyan, red, green or orange, extends the colour gamut that the printer can produce. This means that colours are better replicated and gradations are smoother.

Printing monochrome images

Printing monochrome images is tricky when coloured inks are used, as it is difficult to get a completely neutral mix throughout the tonal range. Printing with just the black ink, however, often takes much longer and the tonal range can be somewhat limited.

Manufacturers can improve this performance by including light black (or more dilute black) in the inkset. This makes it much easier for the printer to reproduce the lighter tones in an image without speckling or banding becoming an issue.

For a while there was a burgeoning business in supplying monochrome inksets. These are banks of cartridges made by third-party suppliers that contain a range of inks with different intensities of black and they are used in place of the manufacturers’ intended coloured and black inks. They vastly improved the monochrome performance of printers with just one black ink. However, once manufacturers began to produce printers with more than one black ink cartridge the need for these specialist sets diminished.

As a rule, the best prints are produced by printers that use a greater number of inks.

Pigment vs dye

Whereas soluble dye gives dye-based inks their colour, pigment-based inks contain finely ground solid colour in suspension. This means that while dye can soak into the print medium, pigment is left on the surface.

A few years ago the results produced by a printer that used pigment-based inks were much easier to distinguish from those made by a printer using dye inks, but today they are a closer match.

Traditionally, dye-based printers produce much more vibrant results, but advances in pigment-ink technology and additional colours in the inkset now enable pigment-ink printers to match them. Metameric failure, which sees prints appear to change colour in different lighting conditions, also used to be more of an issue with pigment inks than it is now.

A key benefit of pigment ink is that it has a very long life, so the prints resist fading for a long time. However, advances in dye technology have given dye-based prints much greater fade resistance.

Dye-sublimation printers

Dye-sublimation printers

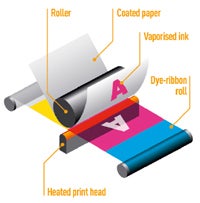

Unlike inkjet printers that use liquid ink, dye-sublimation (or dye-sub) printers are loaded with solid ink on a ribbon or gel.

The solid ink is heated so that it sublimates, or vaporises without going through a liquid phase, and is transported onto the paper. The colour is laid down in three passes, one each for cyan, magenta and yellow.

There is often a fourth pass during which a protective layer is laid onto the print, increasing its resistance to water and scratching.

A key advantage to dye-sub printers is that the ink ribbons contain enough ink for a known number of prints, so you should never run out unexpectedly.