Actually, you can’t get dust on the sensor itself since it lives beneath a protective layer called an Optical Low Pass Filter (OLPF). But ‘dust on the OLPF’ doesn’t have quite the same ring to it.

But the danger is that since this filter sits in front of the focal plane any dust landing on it will be rendered as dark, out-of-focus blobs or lines on the image.

Dust, fluff, grit and other nasties have long been the bane of those working with images. A hair in the gate of a movie camera can ruin feet of stock, while a speck of grit on a lens compromises frames, and can scratch glass. Either way, it’s an expensive nuisance to which none are immune.

Foreign matter is of particular concern to DSLR owners who regularly change lenses because, while the glass is off the body, both the lens and camera’s internals are at risk. Because of this, manufacturers have developed various in-camera methods to fight dust.

Olympus was the first to market with a built-in dust-reduction system in its E-series, then Pentax and Sony followed suit. Canon introduced its own self-cleaning sensor relatively recently, leaving Nikon alone among the main manufacturers in not having an in-camera anti-dust system.

Olympus was the first to market with a built-in dust-reduction system in its E-series, then Pentax and Sony followed suit. Canon introduced its own self-cleaning sensor relatively recently, leaving Nikon alone among the main manufacturers in not having an in-camera anti-dust system.

Olympus’s Supersonic Wave Filter, launched in 2003, works by vibrating dust off the low-pass filter that covers the sensor, and onto a sticky pad below, whenever the camera is switched on.

Olympus DSLRs all feature the technology and the company reports no instances of dust-related repair problems, according to UK spokeswoman Harjit Sohotey. ‘It is not necessary to clean or change the dust collection components after normal use,’ she says. ‘The system can easily deal with the particles that are generated by the shutter operation.’ But for how long will the dust-collection components remain effective? ‘Although it ultimately depends on usage, they will maintain their performance for several years,’ says Harjit. ‘However, we recommend that users send their cameras to one of our service centres at intervals of around three to five y ears and, as part of that process, the dust-collection components would be automatically replaced.’

ears and, as part of that process, the dust-collection components would be automatically replaced.’

Despite maintaining for years that sensor-based anti-dust systems were unnecessary, Canon did a U-turn late last year by incorporating it into their 400D. In a three-pronged attack on this ‘non-existent’ problem, the 400D uses an anti-static coating to repel dust particles from the sensor, and the low-pass filter vibrates whenever power is switched on and off, shaking dust onto, yes, a sticky strip at the bottom. Finally, the camera is bundled with Digital Photo Professional, which, in conjunction with data from the image sensor, can identify specks and automatically erase them from the image.

As for the efficacy of all this dust-busting technology, it’s hard to judge, though a scientific test of anti-dust systems by a French journal found the Olympus system to be the most effective.

Nikon UK’s James Banfield, meanwhile, claims that ‘tests are not necessarily conclusive that anti-dust mechanisms are any more beneficial than ‘good housekeeping’ and reducing the effects

of dust in product design and manufacture’. His opinion may not be entirely unconnected with the fact that Nikon has its own strategy for combating dust that starts in the factory.

Dust in manufacturing

Dust in manufacturing

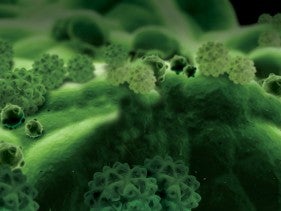

You might think that if you just bought one superzoom lens and never took it off the camera you’d be immune from the dust problem, but even owners of integral-lens cameras can suffer. While manufacturers are careful to keep their production facilities clean, motes can still stray in and settle on the camera’s imaging chip, leaving dark blobs on each image taken.

Understandably, manufacturers are loathe to reveal the exact details of their camera-building methods, but it’s well known that image-sensor chips are made in dust-free environments. A speck of foreign matter will ruin a chip during manufacturing, hence there’s much use of automation, while workers entering a clean area must wear protective clothing to stop hair, skin and other impurities from affecting chip wafers.

Care must still be taken to avoid contamination from the camera’s own mechanical components which, as they wear during normal use, can shed tiny particles that can land on the sensor.

James Banfield offers insight into the company’s own methods of countering dust during the manufacturing process. ‘The shutter unit’s drive mechanism and other moving parts are designed so that as little dust as possible is created with their movement.’ Nikon ‘breaks in’ components before and after assembly inside the camera body to prevent the creation of dust caused by normal wear. ‘Dust does not adhere,’ adds James. ‘The CCD and the OLPF [optical low-pass filter] unit has an anti-static design to prevent the adherence of dust and foreign particles.’

A specialised method is used to absorb dust or foreign particles surrounding the image sensor, and the area surrounding the rear surface of the image sensor is sealed to help prevent dust and foreign matter from entering.

A specialised method is used to absorb dust or foreign particles surrounding the image sensor, and the area surrounding the rear surface of the image sensor is sealed to help prevent dust and foreign matter from entering.

Furthermore, continues James, Nikon cameras are ‘designed to maintain a space between the OLPF and the CCD to reduce the visibility of any dust which may be present’. As for further dealing with the effects of dust: ‘Post-processing using the ‘Dust Off’ feature in Nikon’s optional photofinishing software Capture NX can be used to effectively reduce the effects of dust or foreign objects in Raw images.’

Above: A ‘clean room’ for CCD manufacture at Fujifilm’s factory in Sendai, Japan. Air blown in from the ceiling pushes dust particles through

small holes in the floor to help ensure a dust-free environment